Andrea Vianello, Assurdo Italia, Baldini Castoldi, 2008

The book quoted above deals with some absurd situations which seem to be typically Italian.

I'd like to translate a passage referring to some methods used in Naples to avoid paying fines and penalties. See the original text below.

(pages 77-79)

Furelli [the protagonist of the story] stated that in Naples there were (maybe still there are) many ways not to pay fines.

The first method is that of the dead man: after someone dies, the local camorra boss buys some cars in his name. When those cars get fines, the fines are sent to the dead man's house, but, as we know, dead people cannot pay ...

Another method is that of the 'good' postman: the postman takes a fine to a certain person. The person opens the letter and sees that the amount is too high. The 'good' postman is available to state that the letter was sent to an 'unknown receiver' and the fine is sent back. If a fine is not paid within a certain time for an acceptable reason it is no longer mandatory to pay it. Furelli said that, at that time, 27% of the fines were sent back like this, with good or bad reasons.

Another method was that of the white document. The original fine was copied on a white document: faithfully, except for one or two zeros, which were canceled from the correct amount to be paid. So, if you had to pay 100,000 Lire, the fine could be reduced to 10,000.

In this way local authorities lost most of the sums.

Another method was that of the cheating lawyer. A lawyer or pseudo-lawyer was sent to a public office. He asked to see a document kept in rooms full of papers, and while he was alone in the office he put the fine somewhere out of order so that it would never be found again.

Another method is that of the flood: strangely enough, Furelli said, the store for fines in Naples was moved to an old school in ruin and full of water: the original documents were damaged by water and other liquids used for the building; then they were given to the Red Cross like useless papers.

If the original documents get lost, authorities cannot oblige people to pay the fines.

When Furelli was working in the Town Hall in Naples, in 1994, he could witness the first consequences of the Italian phenomenon 'crazy fines'. By means of computers, fines were recorded in succession up to number 99,000. When fines were hundreds of thousands the succession was interrupted and the list began again with the first numbers 1, 2 ... In this way the previous fines disappeared and were replaced by the new ones.

For local authorities in Naples getting the money for fines and penalties seem to be more difficult than winning the lottery.

____________________________________________________________

Original text:

(pp. 77-79)

Sostiene Furelli infatti che per non pagare una multa a Napoli esistevano (oppure esistono?) molti metodi.

C'era il metodo del morto: un tizio tira le cuoia, il camorrista della zona mette le mani sul suo certificato di residenza e si intestano al deceduto un certo numero di automobili. Così, quando queste compiono un'infrazione, la multa arriva al morto, e si sa che i morti non possono pagare ...

C'era il metodo del portalettere 'buono': arrivato a casa del contravventore, i due controllavano insieme la cifra richiesta e, se era troppo alta, si richiudeva il tutto e si rimandava al mittente con la dicitura 'destinatario sconosciuto', così passavano i tempi previsti per legge e si sperava nella prescrizione. Sostiene Furelli che, all'epoca, il 27% delle multe tornavano indietro, a torto o a ragione.

Poi c'era il metodo del bollettino bianco: con la complitcità di qualche amico nell'ufficio giusto, si trascriveva il verbale su un modulo vergine e si toglieva uno zero. Centomila lire diventavano diecimila, il verbale risultava pagato ma il comune perdeva novantamila lire ..

Poi ancora il metodo dell'avvocaticchio: un legale o un presunto tale andava a chiedere di controllare un verbale, entrava in un archivio più simile a un magazzino impolverato che a un ufficio pubblico efficiente, e in un attimo di distrazione degli addetti, zac! rimetteva il verbale nel posto sbagliato, in pratica facendolo perdere per sempre.

Oppure quello più sistematico, il metodo allagamento: chissà come mai, sostiene Furelli, il centro deposito delle multe di Napoli venne un giorno spostato in una vecchia scuola diroccata, dove periodiche perdite di acqua finirono per danneggiare migliaia e migliaia di multe originali. E quando le rimanenti vennero trasferite in un locale dismesso della prefettura, i lavori di disinfestazione furono compiuti inavvertitamente con l'uso di liquidi corrosivi che distrussero altrettanti verbali, poi consegnati alla Croce Rossa come materiale fuori uso ...

E attenzione, la scomparsa del verbale originario è decisiva in caso di ricorso: il giudice di pace può pronunciarsi a favore del Comune solo se viene esibita la prima contravvenzione. Se questa non c'è, multa annullata, e soldi perduti!

Durante la sua gestione, inoltre, Furelli visse indirettamente nel 1994 anche il primo fenomeno di 'multa pazza' italiana. che fu dovuto proprio all'informatica, anche se non quella gestita da lui: il sistema computerizzato della concessionaria esattoriale era troppo antiquato e aveva un 'baco'. Dopo il numero 99.000 ripartiva da zero: così quando vennero iscritti a ruolo centinaia di migliaia di verbali non pagati, abbinando in ordine progressivo il numero di verbale al rispettivo contribuente, arrivati a centomila si ricominciò inavvertitamente da capo, e i primi della lista si ritrovarono appioppati verbali non loro, e giù per li rami. Grande scandalo, grandi proteste, e tantissime altre multe annullate.

Insomma, incassare una multa a Napoli era per il Comune proprio come vincere un terno al lotto.

Personal blog in English. If you want to leave a comment, write to barazza.roberta@gmail.com

About Me

ruins

country house

novi mesto (slovenia). commercial center

warsaw. iceskating little rabbit

viterbo (italy). shop

udine. helicopter

udine. tractor

motovun (croatia)

krasica (croatia)

church in slovenia

slovenia

armour

rome. palm tree

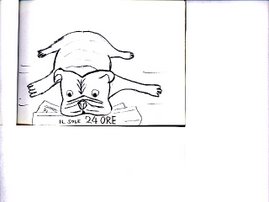

dog carrying a newspaper

rome. campo dei fiori. giordano bruno's statue

rome. Palazzo Venezia